Scratch a big item off the bucket list! I finally got the chance to visit the ruins of Chichén Itzá which is is one of the New Seven Wonders of the World and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

I booked a day long excursion from our resort in Cancun to visit this historic Mayan city. Our group left around 7 AM for a three hour drive to the site. The bus made one stop for lunch and souvenir shopping at a rustic village and plaza not too far from Chichén Itzá. Unfortunately, we only had two hours at the site itself as Mexican law restricts tour buses to a strict time limit at historic sites which receive millions of visitors annually. Two hours is nowhere near enough time to explore the site and if you are late, the bus will leave without you. During the first hour, our excellent tour guide gave a very informative presentation on the Temple of Kukulcán and the Mayan ball court. The remaining hour was unguided and that left insufficient time to explore the Temple of a Thousand Warriors and other landmarks. The best way to visit Chichén Itzá is to book a nearby hotel and spend a day or more onsite.

Disclaimer: Due to time constraints, I was unable to photograph several key landmarks, so I used images from wikipedia to fill those gaps. My own images are identified by name in the lower right corner. Images not bearing my name are from Wikipedia or stock photos.

A Brief History

Chichén Itzá was a large pre-Columbian city built by the Maya people of the Terminal Classic period. It is located in the Tinúm Municipality of Yucatán State, Mexico. It was a major focal point in the Northern Maya Lowlands from the Late Classic (c. AD 600–900) through the Terminal Classic (c. AD 800–900) and into the early portion of the Postclassic period (c. AD 900–1200). The site exhibits a multitude of architectural styles, reminiscent of those seen in central Mexico as well as the Puuc and Chenes styles of the Northern Maya lowlands. The presence of central Mexican styles was once thought to have been representative of direct migration or even conquest from central Mexico, but most contemporary interpretations view the presence of these non-Maya styles as the result of cultural diffusion.

Chichén Itzá was one of the largest Maya cities and it was likely to have been one of the great mythical cities or Tollans, referred to in later Mesoamerican literature. The city may have had the most diverse population in classical Mayan world which is a factor that may have contributed to the variety of architectural styles at the site. It is estimated that only 3.5% of Chichén Itzá has been excavated – this gives one a sense of just how large the original city would have been. When constructed, these limestone buildings were covered by plaster and painted in vivid colors. Over time, nearly all the plaster has eroded and if one looks closely at my photos, you can see a few remaining bits of colour on the stones.

The Temple of Kukulcán Pyramid

Built by the pre-Columbian Maya civilization sometime between the 8th and 12th centuries AD, the building served as a temple to the deity Kukulcán, the Yucatec Maya Feathered Serpent deity closely related to Quetzalcoatl, a deity known to the Aztecs and other central Mexican cultures of the Postclassic period. It has a substructure that likely was constructed several centuries earlier for the same purpose. Although significantly smaller than the great pyramids of Giza, the Temple of Kukulcán is still a rather imposing structure measuring 30 m (98 ft) high with a base of 55.3 m (181 ft).

The Temple of Kukulcán was used as an astronomical calendar to indicate when to plant and harvest crops . The pyramid-shaped structure was constructed with four staircases, each consisting of 91 steps and a platform at the top, making a total of 365 steps. This design was intentional and significant because it represented the number of days in a solar year. Additionally, during the spring and autumn equinoxes, the sun casts a shadow on the staircase that resembles a serpent descending down the pyramid terminating at a stone carving of Kukulcán at the base. This phenomenon was likely used by the Maya to mark the changing seasons and agricultural cycles. As there is no topsoil in the Yucatan region of Mexico, Mayan agriculture relied on cutting down forests and burning trees to create a suitable area for planting their crops. Historians believe the temple served as an astronomical calendar to indicate the beginning of the rainy season which signals when ancient Mayans would cut down forests and plant crops.

The Golden Ratio

Pay close attention to the doorway located at the top of the temple as it is not perfectly centered. The Mayans believed Kukulcán travelled between the underworld and the heavens through a portal. The off-center door at the top of the pyramid represents this portal and it is aligned slightly to the north. It also allowed priests to use the changing positions of the sun during the solstices and equinoxes to create a visual effect of the feathered serpent descending down the pyramid’s stairs.

Our tour guide pointed out the doorway is offset to a ratio of 1.6 and that is quite significant. The ratio 1.6, also known as the Golden Ratio or the Divine Proportion is concept in mathematics associated with natural beauty and divine proportions. It was called the extreme and mean ratio by Euclid and the Divine Proportion by Italian Mathematician Luca Pacioli. Usually written as the Greek letter phi, it is strongly associated with the Fibonacci sequence, a series of numbers wherein each number is added to the last. The Fibonacci numbers are 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, and so on, with the ratio of each number and the previous number gradually approaching 1.618, or phi. The Mayans found the golden ratio present in the orbits of planets; they accurately computed the solar orbit of Venus which lasts 225 days and they also knew the Earth takes 365 days to orbit the sun. If you divide 365 by 225 you get 1.62 and that factored into Mayan religious ceremonies and symbolism. In many ways the Mayan numbering system was superior to what existed in the West prior to 1200 AD. The main reason is after 400 AD the Mayans used zero in their calculations and there is no zero in roman numerals. Other cultures discovered zero, but it was not incorporated into European mathematics until circa 1200 AD when Italian mathematician Fibonacci (aka Leonardo of Pisa) brought it, along with the rest of the Arabic numerals, back from his travels in north Africa.

Mayan Ballcourts and Sacrificial Players

Archeologists have identified thirteen ballcourts in Chichén Itzá for playing the Mesoamerican ballgame. The Great Ball Court situated approximately 150 meters (490 ft) to the north-west of the Castillo is the largest and best preserved ball court in ancient Mesoamerica measuring 168 by 70 meters (551 by 230 ft). The parallel platforms flanking the main playing area are each 95 meters (312 ft) long. The walls of these platforms stand 8 meters (26 ft) tall and high up in the center of each of these walls are rings carved with intertwined feathered serpents. Little is known about the rules of Mayan ball games, but it is generally accepted that scoring was made by passing a rubber ball through these rings.

According to MIT researchers, ancient Mayans used bouncy vulcanized rubber balls, resilient rubber sandals and a sticky material used to glue implements to handles. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of years ago, the Mayans perfected a system to vulcanize natural rubber. Without vulcanization, natural latex is too brittle for practical use. The Mayan process to vulcanize rubber is still unknown, although there are some working hypotheses. Bear in mind the modern process to vulcanize rubber was patented in 1844 by Charles Goodyear thereby making it possible to use rubber in car tires, bouncing balls and much more.

Look carefully at this modern mural depicting a Mayan ball game, it is rich in symbolism and reflects the central Mayan themes of darkness and light. It is split evenly between night and day, the moon and the sun. One of the players is about to score by bouncing a rubber ball off his hips into the serpent ring located 8 meters (26 feet) high. It is widely believed the game was played without hands and players used their knees, hips and elbows to move the ball.

In the middle of the mural, there is a bat and a decapitated player. The bat represents a key figure of the underworld: Camazotz (aka Zotzilaha Chamalcan). The name Camazotz translates to either ‘death bat’ or ‘snatch bat’. In Mesoamerica the bat is often associated with night, death, and sacrifice. It is widely accepted that sacrifices were offered in these sacred ball games, however there is much debate about who was sacrificed and how often it occurred. At one time, historians believed the losing team was sacrificed, but that perspective has been challenged and emerging theories postulate the captain of the winning team was sacrificed by decapitation and disembowelment. The incentive is great honour was placed on the individual and their families leading to advancement in Mayan society and greater social status. Moreover, some historians suggest that a sacrifice of the best players was a better offering to the gods. There is also speculation the losing team would suffer demoted status or impoverished slavery.

Note the presence of a jaguar figure in the mural. Mayans believed at night the sun, as it slips into the underworld, would transform into a jaguar. The jaguar was also associated with warriors and hunters, and became a symbol of the might and authority of Mayan rulers.

Tzompantli – Platform of the Skulls

The Tzompantli is a rectangular platform measuring 60 meters (197 feet) by 12 meters (39 feet). A central band decorated with skulls runs in three horizontal rows and at the top there is a slightly tapered band with another row of skulls. It is believed this platform was used to memorialize past war victims as well as display the heads of sacrificial prisoners or enemies that died in battle. Built to display the conquests of the state, it may have been used to control the population and frighten enemies. This monument gives evidence to the practice of human sacrifice for religious-military ends by Chichén Itzá’s ruling class.

Templo del Hombre Barbado (Temple of the Bearded Man)

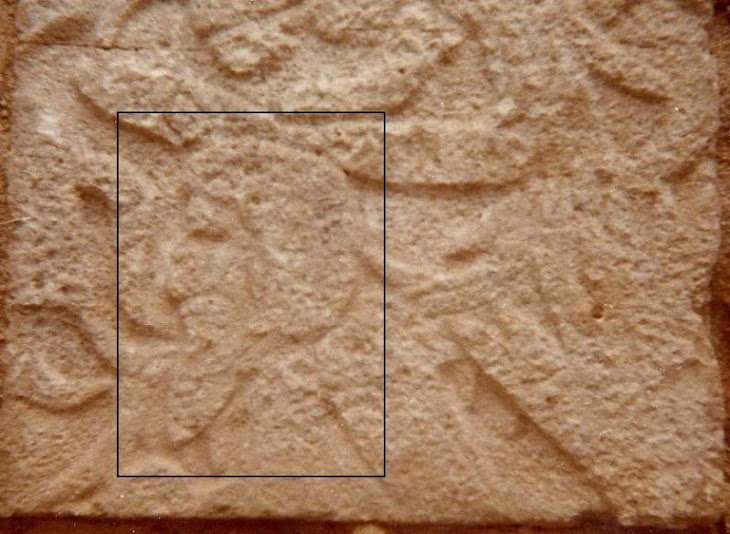

At one end of the Great Ballcourt at Chichén Itzá is the North Temple, also known as the Temple of the Bearded Man. On the back wall of this structure there is a portrayal of a tall, fair-skinned, bearded figure that differs from the typical portrayal of Mayan warriors and priests. Depictions of bearded men are extremely rare in Mayan art and their presence at Chichén Itzá remains a mystery. Throughout the years there has been speculation as to the origin and meaning of this image. One account attributes the bearded figure to a Toltec chieftain who conquered the Yucatan. It is said he was bearded and fair-skinned, with his symbol being a feathered serpent. Other stories which have come down through the years spoke of visitations by fair-skinned bearded divinities. Another theory says this is the personification of Kukulcán, the god who came from the west and brought knowledge to the Mayan people of Yucatan. Our tour guide suggested that Mayans may have been visited by Vikings prior to the arrival of Spanish Conquistador Hernán Cortés in 1519. Evidence for any of these theories remains sketchy at best. Straining credulity to the point of absurdity, some Christians have suggested the bearded figure is a resurrected Jesus Christ visiting Mesoamerica.

Due to renovations, I was unable to capture an image of the mysterious bearded figure on the temple. For reference here is a stock image.

Plataforma de Venus (Venus Platform)

Shining brightly, Venus is first “star” to appear in the sky after sunset or the last to appear after sunrise depending on the time of year. The Mayans studied and tracked Venus extensively as it was considered a sacred heavenly body and an astronomical measuring point. The Dresden Codex, one of three paper-bark books that survived the mass destruction of documents by Spanish religious zealots in 1562, is filled calculations for lunation cycles and Venus tables. Venus was used to help establish the Mayan Calendar for agricultural and ritual planning. Little is known about this building, however, it has been suggested it may have functioned as a podium for for religious rites, ceremonies or dances. There are glyphs at each of the corners representing signs of Venus in the form of a year symbol, half flower with crosses on the petals. Mayan astronomers also tracked the movements of Mercury, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn.

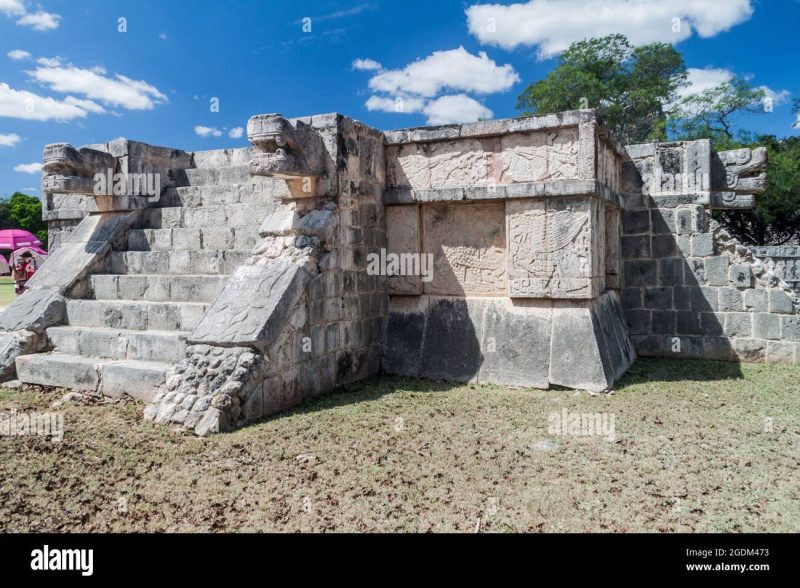

Plataforma de las Águilas y los Jaguares (Eagles and Jaguars Platform)

One of the smaller structures at Chichén Itzá, the Eagles and Jaguars Platform is a structure with staircases on all four sides. The stair rails are topped with the serpent god Kukulcán. On the walls of the structure are prostrate human figures and underneath them are Eagles and Jaguars grasping human hearts. The figures of jaguars and eagles devouring hearts are believed to represent warriors who were responsible for obtaining victims to sacrifice for the gods. The “Eagle Knights” were Mayan archers who attacked the enemy before soldiers fought hand to hand. The aggressive eagles which sculpted on the walls of the platform represent these archers who stood out on the battlefield as they wore clothing made from eagle feathers. The platform was likely used for religious and ceremonial purposes with an emphasis on military power.

Templo de los Guerreros (Temple of a Thousand Warriors) – The complex I did not explore

As mentioned above, our tour was limited to a mere two hours and that left no time to properly explore or photograph the Temple of a Thousand Warriors. I saw it in the distance took two photos, looked at how much time I had left and made my way back to the bus with 10 minutes to spare. For the purposes of this blog post, I used additional images from Wikipedia and did my own homework to learn about this structure as it was not part of the guided tour.

The Temple of the Warriors complex consists of a large stepped pyramid fronted and flanked by rows of carved columns depicting warriors. It is similar to Temple B at the Toltec capital of Tula and is thought to indicate some form of cultural contact between the two regions. However, these traits of cultural similarity are a point of controversy among scholars. Some argue the Toltecs invaded Maya and made Chichén Itzá their new capital, others argue for a migration of Toltecs to Maya leading to a peaceful exchange of culture and architecture. A new theory argues for the separation of both cultures and suggests the mixed style of architecture at Chichén Itzá was constructed without Toltec influence. Through carbon dating, it was discovered that the ‘Mexicanized’ and pure Maya sites had been constructed at the same time. Second, it was learned that most of these sites were constructed before any recorded major Toltec influence occurred.

Along the south wall of the Temple of Warriors are a series of exposed columns, when the city was inhabited they would have supported an extensive roof system. A north group facing ruins along the south wall of the Temple of Warriors and contains pillars with carvings of soldiers in bas-relief. A northeast group, which formed a small temple at the southeast corner of the Temple of Warriors, contains a rectangular area decorated with carvings of people and/or gods as well as animals and serpents.

Cenote Oxman and Valladolid

Before returning to the resort, our tour bus made two stops. One at the Cenote Oxman and all too brief stop in the beautiful Spanish colonial town of Vallodolid. Cenote are water filled sinkholes that occur naturally with limestone rock when an underground cave collapses and exposes the groundwater underneath. Mayans believed cenotes to be a gateway to the underworld of Xibalba. Chaac, the god of rain, was believed to live at the bottom of these sacred wells. The Maya performed rituals and ceremonies at sacred cenotes to ask for rain and good crops. Cenotes were also an important source of water for drinking and hydrating crops. There are thousands of cenotes dotted around the Yucatan Peninsula and many are popular tourist sites. A few people on the tour brought bathing suits and towels to swim in the Cenote, I did not. In hindsight I made the right choice as it was too crowded and unsacred for my liking.

Our final destination was a very brief 20 minute stop in the colonial town of Vallodolid. With little time available, I walked around the town square snapping a few photos and making damned sure I did not miss the bus. Named after Valladolid, the former capital of Spain, the town was established by Spanish Conquistador Francisco de Montejos, aka “the Nephew”, in 1543. One building caught my eye and that was the Cathedral De San Gervasio. Originally built in the 16th century, the cathedral was constructed with parts of ancient Maya temples and buildings after Spain invaded and destroyed them in their efforts to colonize and convert the Maya to Catholicism. The current church was erected at the start of the 18th century since the original building was destroyed after it was the site of political unrest. The current church still incorporates stones taken from Mayan buildings and temples.

Perhaps I shall return to Chichén Itzá another day and book a nearby hotel. There is so much more I wanted to see and two hours onsite barely skimmed the surface. Click any thumbnail below to see the photo gallery.

#ChichénItzá #ChichenItza #Yucatan #Mexico #Mayan #Kukulcán #Kukulcan #Maya #Mayans